Category Uncategorized

Superheroes inspired by Islam

How do you explain the work of an interculturalist?

If you read this blog you probably know that I work in the intercultural field. While I really enjoy my job as a trainer, coach and consultant, it isn’t always easy to explain to others what this line of work consists of. The “uninitiated” rarely have a feel for what we interculturalists do.

This became even more apparent to me after seeing a discussion in one of the LinkedIn groups I’m following. Vanessa Shaw posted a question in the SIETAR Europe group called Competence in intercultural professions that prompted me to post a comment.

Vanessa asked: “What’s your elevator speech to explain the intercultural field? The term ‘intercultural’ is still not known widely – how do you describe the ‘intercultural field’ to others in a quick elevator speech? I’m trying to formulate a more concise answer myself, and it’s hard to narrow it down.“ This was my answer:

Going by the number of “likes” I received for this suggestion, I suppose my 30-second pitch might also work for others in the field. However, I caution everyone when trying to use it in a global context. It simply won’t work in every culture.

My other favorite line is: I help others build solid transatlantic bridges.

As Bill Reed remarked in the conversation: “In several Japanese companies I know, it is explicitly forbidden to speak in a lift (an elevator).”

And Paul Miles is also correct when he says: “In countries where English is a second language, ‘I’m an interculturalist’ would be met with a blank expression.”

David Patterson, who I assume is British, also reminded me that elevator speeches aren’t always well received in German-speaking cultures: “For example, has anyone else ever tried doing an Anglo-saxon style presentation e.g. (‘I have copies of the market research detail for those who would like to study it at their leisure, here are the key highlights for your decision’) to a German audience of senior management? Doesn’t play well at all – you need to demonstrate your professional competence by showing us the work you have done and being ready to answer detailed questions on your methodology and recommendations.”

Of course, David is right about the differences in presentation styles – some cultures find the idea of an over-simplified message dubious or untrustworthy. But here’s the thing: Even in Germany you have to initiate a business conversation at an entry level. Nobody will listen to your elaborate 30-minutes (or more) sales pitch if you can’t interest them in what you are doing/selling.

Which brings us back to the initial question: What is it we interculturalists do? You have 30 seconds. Go!

THE CULTURE IN THE COCKPIT

Did Korean culture affect plane crash?

CNN about the great importance of good communication in the cockpit.

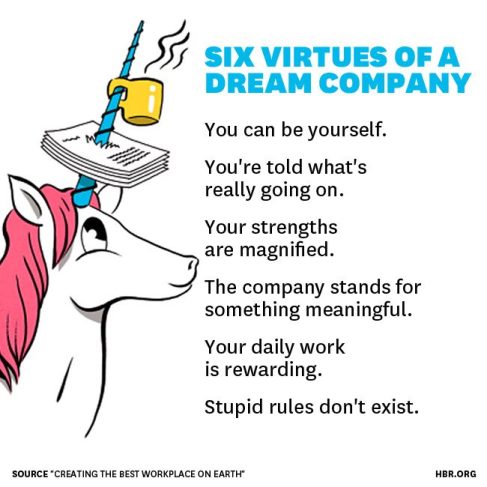

Creating the Best Workplace on Earth

by Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones

Suppose you want to design the best company on earth to work for. What would it be like? For three years we’ve been investigating this question by asking hundreds of executives in surveys and in seminars all over the world to describe their ideal organization. This mission arose from our research into the relationship between authenticity and effective leadership. Simply put, people will not follow a leader they feel is inauthentic. But the executives we questioned made it clear that to be authentic, they needed to work for an authentic organization.

What did they mean? Many of their answers were highly specific, of course. But underlying the differences of circumstance, industry, and individual ambition we found six common imperatives. Together they describe an organization that operates at its fullest potential by allowing people to do their best work.

We call this “the organization of your dreams.” In a nutshell, it’s a company where individual differences are nurtured; information is not suppressed or spun; the company adds value to employees, rather than merely extracting it from them; the organization stands for something meaningful; the work itself is intrinsically rewarding; and there are no stupid rules.

The “Dream Company” Diagnostic

How close is your organization to the ideal?

To find out, check off each statement that applies. The more check marks you have, the closer you are to the dream.

Let Me Be Myself

☐ I’m the same person at home as I am at work.

☐ I feel comfortable being myself.

☐ We’re all encouraged to express our differences.

☐ People who think differently from most do well here.

☐ Passion is encouraged, even when it leads to conflict.

☐ More than one type of person fits in here.

Tell Me What’s Really Going On

☐ We’re all told the whole story.

☐ Information is not spun.

☐ It’s not disloyal to say something negative.

☐ My manager wants to hear bad news.

☐ Top executives want to hear bad news.

☐ Many channels of communication are available to us.

☐ I feel comfortable signing my name to comments I make.

Discover and Magnify My Strengths

☐ I am given the chance to develop.

☐ Every employee is given the chance to develop.

☐ The best people want to strut their stuff here.

☐ The weakest performers can see a path to improvement.

☐ Compensation is fairly distributed throughout the organization.

☐ We generate value for ourselves by adding value to others.

Make Me Proud I Work Here

☐ I know what we stand for.

☐ I value what we stand for.

☐ I want to exceed my current duties.

☐ Profit is not our overriding goal.

☐ I am accomplishing something worthwhile.

☐ I like to tell people where I work.

Make My Work Meaningful

☐ My job is meaningful to me.

☐ My duties make sense to me.

☐ My work gives me energy and pleasure.

☐ I understand how my job fits with everyone else’s.

☐ Everyone’s job is necessary.

☐ At work we share a common cause.

Don’t Hinder Me with Stupid Rules

☐ We keep things simple.

☐ The rules are clear and apply equally to everyone.

☐ I know what the rules are for.

☐ Everyone knows what the rules are for.

☐ We, as an organization, resist red tape.

☐ Authority is respected.

These principles might all sound commonsensical. Who wouldn’t want to work in a place that follows them? Executives are certainly aware of the benefits, which many studies have confirmed. Take these two examples: Research from the Hay Group finds that highly engaged employees are, on average, 50% more likely to exceed expectations than the least-engaged workers. And companies with highly engaged people outperform firms with the most disengaged folks—by 54% in employee retention, by 89% in customer satisfaction, and by fourfold in revenue growth. Recent research by our London Business School colleague Dan Cable shows that employees who feel welcome to express their authentic selves at work exhibit higher levels of organizational commitment, individual performance, and propensity to help others.

Yet, few, if any, organizations possess all six virtues. Several of the attributes run counter to traditional practices and ingrained habits. Others are, frankly, complicated and can be costly to implement. Some conflict with one another. Almost all require leaders to carefully balance competing interests and to rethink how they allocate their time and attention.

So the company of your dreams remains largely aspirational. We offer our findings, therefore, as a challenge: an agenda for leaders and organizations that aim to create the most productive and rewarding working environment possible.

Let People Be Themselves

When companies try to accommodate differences, they too often confine themselves to traditional diversity categories—gender, race, age, ethnicity, and the like. These efforts are laudable, but the executives we interviewed were after something more subtle—differences in perspectives, habits of mind, and core assumptions.

The vice chancellor at one of the world’s leading universities, for instance, would walk around campus late at night to locate the research hot spots. A tough-minded physicist, he expected to find them in the science labs. But much to his surprise, he discovered them in all kinds of academic disciplines—ancient history, drama, the Spanish department.

When Crossing Cultures, Use Global Dexterity

When Crossing Cultures, Use Global Dexterity

by Andy Molinsky | 9:00 AM March 12, 2013

Picture the following: Greg O’Leary, a 32-year-old mid-level manager, is in Shanghai for the first time to negotiate a critical deal with a distributor. To prepare himself for the trip, Greg has learned some key cultural differences between China and the U.S. — about how important deference and humility are in Chinese culture, and how Chinese tend to communicate more indirectly than Americans do. He also has learned about how important it is in China to respect a person’s public image or “face.” Finally, Greg also learned a few Chinese words, which he thought could be good potential icebreakers when starting a meeting.

Picture the following: Greg O’Leary, a 32-year-old mid-level manager, is in Shanghai for the first time to negotiate a critical deal with a distributor. To prepare himself for the trip, Greg has learned some key cultural differences between China and the U.S. — about how important deference and humility are in Chinese culture, and how Chinese tend to communicate more indirectly than Americans do. He also has learned about how important it is in China to respect a person’s public image or “face.” Finally, Greg also learned a few Chinese words, which he thought could be good potential icebreakers when starting a meeting.

Greg quickly realizes, however, that learning cultural differences in theory does not always translate into successful behavior in practice. The first problem comes when Greg, who is praised for his “excellent Chinese,” proudly accept the acknowledgement, not realizing how publicly expressing pride in this way runs counter to the important role of humility in Chinese culture and could come across as arrogant to his Chinese counterparts. He then quickly backtracks and deflects the praise, but feels awkward and clumsy doing so. Next, Greg tries to use a more indirect communication style to impress his colleagues. But here again, Greg struggles. Greg is such a straight shooter by nature that it feels awkward and evasive not to say what he means. He also has no clue how indirect he should be. By the end, it becomes frustrating, and all Greg wants to do is end the conversation.

This situation highlights a challenge that global leaders and managers constantly face in their global work: The way that you need to behave to be effective in a new setting is different from how you’d naturally and comfortably behave in the same situation at home.

I’m sure that this isn’t news to any of you. Many of us have lived, worked, or studied abroad, and if you haven’t, you’ve certainly read one of the many books or articles describing cultural differences. But what these books don’t tell you is that learning about differences across cultures is only a first step toward effective cultural adaptation, and if all you do is learn differences, you will likely suffer the same fate as Greg. It’s not only the differences that most people need to understand to be effective in foreign cultural interactions: It’s global dexterity, the ability to adapt or shift behavior in light of these cultural differences. And that’s something that’s often easier said than done.

Why? Well, for starters, it’s often very difficult to perform behaviors you aren’t used to, even if you have an intellectual understanding of what these behaviors are supposed to be. From my work interviewing and working with hundreds of professionals from a wide range of different countries and cultures, I find that it is very common to feel awkward, inauthentic, or even resentful when trying to adapt behavior overseas. And when you have such strong internal reactions to adapting cultural behavior, your external performance can suffer. The negative feelings can leak into your performance and make you look awkward or unnatural. They can also cause you to want to avoid these situations altogether — in a similar way that by the end of Greg’s conversation, he just wanted it to end.

Now of course, not all situations are so difficult. Some situations — like, say, learning to kiss on two cheeks for an American in Europe (or three or four, depending on where you are) — are a bit unusual, but don’t feel deeply disingenuous to do. But many other situations — like giving performance feedback, participating in a meeting, delivering bad news, interviewing for a job, or promoting yourself or your product — require behavior of you that simply is much harder to perform. And these very same situations are also often critical to your success in a foreign culture. So how can you learn to adapt behavior successfully without feeling like you are losing yourself in the process? Here are a few quick tips:

First, make the behavior your own. Behaving in a new culture isn’t like hitting the bull’s-eye of an archery target. In many cultures and in many situations, you have leeway to adjust, and by doing this smartly, you can achieve success without compromising your authenticity. For example, instead of saying something like, “No, no, my Chinese is very poor” (a prototypical Chinese response), Greg might have tried something like, “Thank you. I have been trying hard to learn, but my Chinese is still very poor.” This is a cultural blend — a hybrid. It mixes Chinese humility with a bit of pride, acknowledging that he has been trying hard to learn the rules. Now in some places and contexts in China, this might not work; it might seem too Western. But in other places, it might.

That’s where a cultural mentor comes in: someone capable of telling you whether these changes work in the new setting. Now, remember that it’s not all of China Greg needs to worry about; it’s the specific people he’s interacting with. So, find a mentor who is familiar with China or the culture you’re operating in, but also someone familiar with your particular work environment. For example, perhaps Greg is interacting with 20-somethings who did their MBA in the States and have a Western approach. Or perhaps they’re employees of a state-run enterprise with a very traditional background and set of expectations. Knowing this is critical when learning to customize your behavior.

So too is assessing internally how comfortable it feels to make these adjustments. Perhaps the adjustments are good externally, but feel wrong, inappropriate, or inauthentic internally. That’s ultimately no good for you because the discomfort you experience will likely leak into your performance and make it hard to perform the behavior authentically, which is key for forging relationships in any culture. You’ll have to break out of your comfort zone to some degree, but make sure you still retain who you are.

The final piece of advice is to develop a forgiveness strategy. You will make mistakes as you experiment with cultural adaptation. Do what you can to not be punished for them! Signal to others that you’re trying to learn their cultural rules, even though you haven’t yet mastered them, and that you care about and respect their traditions. That will go a long way toward building cultural capital that you can cash in in any foreign setting.

Research Findings: The Value of Intercultural Skills in the Workplace

Virtual / Intercultural Team management

By LYNDA GRATTON

Around the world, a wide range of corporate tasks are being performed by teams of employees who rarely if ever meet in person.

The rise of so-called virtual teams is hardly surprising, given the vast investments corporations are making in internal communications and networks. Technically, it’s no longer a challenge to work closely with colleagues in distant locations or to hold meetings with participants scattered around the globe.

Wall Street Journal Video

WSJ’s Carol Hymowitz interviews Lynda Gratton, professor of management at the London Business School, about the challenges of managing a virtual team and how Nokia sets an example.

In practical terms, however, plenty of hurdles remain. Among them: time-zone differences that make quick exchanges difficult, and cultural miscues that can cause misunderstandings. Teams that don’t meet in person are considered less likely to develop the kind of chemistry seen in teams that do — an element that’s often seen as a key factor in making teams productive.

A recent study of virtual teams at multinational companies — teams ranging in size from four to nearly 200 — found that many of the groups were beleaguered by just these kinds of long-distance challenges, to the point of being in continuous danger of breaking up. Other virtual teams, meanwhile, were high performers, virtual hot spots of innovation and energy.

Why does one virtual team thrive while another stumbles? What differentiates the two?

It’s an important issue, as companies become more reluctant to bear the expense of frequent in-person meetings — and employees increasingly resent the burdens travel places on their health and personal lives. Finding a way to make virtual teams work better is therefore crucial if companies are going to get the most productivity out of their far-flung work force.

Join the Discussion

Have you or your company set up a virtual team? If so, what are some of the main obstacles the team has faced? And how has the team helped improve overall output? Join London Business School’s Lynda Gratton in an online forum.

This research began with in-depth case studies of successful virtual teams at a number of companies, including BPBP +2.71% PLC, Nokia Corp.NOK -3.48% and Ogilvy & Mather, a unit of WPP Group PLC. In addition, a research team at London Business School surveyed more than 1,500 virtual-team members and leaders from 55 teams across 15 European and U.S. multinational companies.

Based on our findings, we have identified certain traits and practices common to the most successful virtual teams and their employers. Here, then, are 10 golden rules for making virtual teams more productive:

1. Invest in an online resource where members can learn quickly about one another.

Because of their physical separation, one of the biggest challenges virtual-team members face is an inability to easily learn about one another and what each person brings to the project. Online tools can help, in the same way that social-networking Web sites help college and high-school students get to know other members of their communities. Our research showed that such practices are often unfamiliar to those who graduated from college years ago, but they can be enormously powerful when used in virtual teams.

Take the advertising company Ogilvy & Mather. Its late founder, David Ogilvy, placed enormous emphasis on sharing knowledge within the company. More than a decade ago he invested in an internal IT-based community he called Truffles. As a gourmet, Mr. Ogilvy appreciated the rich taste of a truffle, and he believed that people should search for knowledge with as much energy and enthusiasm as a pig searches for truffles in the oak forests of France.

Truffles gives access to shared projects and a database of company knowledge. It provides forums for the many hundreds of communities of interest that have sprung up in the firm, where ideas and insights are shared. Truffles also features a detailed and frequently updated directory of all Ogilvy employees, giving each an opportunity to list the aspects of work that he or she is passionate about.

![[image]](https://i0.wp.com/sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/it_pj-globe-arrow203242006143410.gif)

Far Sighted

The Situation: While technology makes it possible for teams spread around the world to collaborate on projects, relying solely on electronic communications has its shortcomings.

What Doesn’t Work: Members of so-called virtual teams often tend not to develop the desired chemistry due to their physical separation, lack of familiarity and distant time zones.

Making It Work: Successful virtual teams share common traits, such as social-networking tools and the right mix of members, some of whom are already acquainted and others not.

Such capabilities help ensure that even virtual-team members can rapidly get to know something about one another. For instance, when a big Ogilvy client wants to launch an ad campaign simultaneously in all of its global markets, a virtual team can start working together effectively within days.

2. Choose a few team members who already know each other.

Virtual teams are much more likely to be productive and innovative if they include some people who already know each other. So-called heritage relationships are crucial to rapidly building networks among the team members.

A word of warning, though: If a majority of the people on a team already know each other, the team can become stale and predictable. It’s often through the unexpected insights of new colleagues that innovation is sparked.

3. Identify “boundary spanners” and ensure that they make up at least 15% of the team.

Boundary spanners are people who, as a result of their personality, skills or work history, have lots of connections to useful people outside the team. BP has a long history of colleagues from different business units working together to span the corporate boundaries that separate them.

Customizing Human Resources

PODCAST: “Virtual” teams are playing a larger role at international companies. Lynda Gratton, Professor of Management at the London Business School, tells the Journal’s Carol Hymowitz about some of the challenges of managing this type of team. Listen Now | RSS Feed | iTunes Archive

Another word of warning, though: Having too many boundary spanners risks giving the team so many connections to the outside that it loses its sense of identity and its shared goal.

4. Cultivate boundary spanners as a regular part of companywide practices and processes.

The networking role that boundary spanners play — not just on virtual teams but in the company at large — is so important that companies should try to keep them in continuous supply.

At Nokia, for example, a huge range of routines and processes support and encourage employees to expand their personal networks. To start with, new hires are formally introduced to at least 10 people both within and outside of their departments. It’s an effort that extends outside the company as well. Nokia has strong working relationships with the faculties of more than 100 universities, co-hosting conferences, sharing research initiatives and supporting postgraduate work.

Growing boundary spanners throughout the company helps ensure that when virtual teams are pulled together, at least some of the members likely will have met before.

5. Break the team’s work up into modules so that progress in one location is not overly dependent on progress in another.

Coordinating work across distant time zones can be a continuing battle. Many teams we studied sank into acrimony as one part of the team waited for another to complete part of a task, or as one group worked faster than another.

The Journal Report

Seven myths about outsourcing. Plus, when negotiating a merger, leave a seat at the table for a marketing expert.

- See the complete Business Insight report.

For Further Reading

These related articles from MIT Sloan Management Review can be accessed online

- Improving the Performance of Top Management Teams

By Andrew J. Ward, Melenie Lankau, Allen C. Amason, Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld and Bradley R. Agle (Spring 2007 issue)

The greater the perceived difference in organizational values among members of a top management team and their CEO, the greater the conflict.

http://sloanreview.mit.edu/smr/issue/2007/spring/13/

- The Comparative Advantage of X-Teams

By Deborah Ancona, Henrik Bresman and Katrin Kaeufer (Spring 2002)

Researchers outline the five components of successful teams: external activity, extensive ties inside and outside the company, expandable tiers of responsibility, flexible membership and execution mechanisms.

http://sloanreview.mit.edu/smr/issue/2002/spring/3/

- Building an Effective Global Business Team

By Vijay Govindarajan and Anil K. Gupta (Summer 2001)

Executives guiding global teams must institute processes that emphasize the cultivation of trust and minimize the hindrances to communication caused by geographical, cultural and language differences.

http://sloanreview.mit.edu/smr/issue/2001/summer/6/

- How To Lead a Self-Managing Team

By Vanessa Urch Druskat and Jane V. Wheeler (Summer 2004)

The external leaders of self-directed teams must excel at one skill: managing the boundary between the team and the larger organization.

http://sloanreview.mit.edu/smr/issue/2004/summer/10/

Whenever possible, assign tasks to team members in different locations that allow them to move ahead at their own pace. Depending on the type of work, try designing the work flow so that contributions from different locations can be assembled into a whole toward the end of the process.

6. Create an online site where a team can collaborate, exchange ideas and inspire one another.

Strong virtual teams often have a shared online workspace that all members can access 24 hours a day. This ensures that while different team members or groups are working relatively independently at times, they can continuously follow the progress and insights of other team members.

At Ogilvy, Truffles includes sites dedicated to individual projects in which virtual teams are able to share their plans, modify a shared piece of work, and informally exchange ideas. This ensures that at any time, people can rapidly understand where their own work is, and how it fits with that of others.

7. Encourage frequent communication. But don’t try to force social gatherings.

Members of successful teams communicate with one another often. Interestingly, the mode of communication doesn’t seem to be important. At Nokia, for example, the preferred communication tool was text messaging, while in other companies it was email or voice mail. What is most important is that communication be frequent and rapid.

We encountered few negative comments about the amount of communication that went on — although conventions about the use of e-mail were much appreciated. At BP, for example, team members said that a whole set of rules, such as who should receive emails, who is copied and expectations of reply time, made it easier to work together.

Similarly, a few simple rules can be applied to team gatherings. Virtual teams often make an effort to get the members together at some point during an assignment. We discovered that the timing of such events can be crucial to their success.

Meetings with a strong social element can be resented, for example, when held early in the team’s existence. It seems that in the early phases, creating exciting work with a meaningful goal is seen as more useful than hosting social events. But once the virtual team is up and running and has begun to establish a shared working style, then a collective event can play a key role in the building of trust and goodwill.

8. Assign only tasks that are challenging and interesting.

Because the work of virtual teams is often unsupervised, their tasks should be stimulating and challenging — otherwise the team risks disintegrating under the weight of uninterest.

Indeed, we found that one of the biggest reasons virtual teams fail is because the members don’t find the work interesting. They simply fade away, with fewer and fewer dialing into the weekly conference calls or posting ideas on the shared site. It’s not that the members don’t like one another. It’s simply that the atmosphere becomes more like a country club than a dynamic collection of inspired people.

9. Ensure the task is meaningful to the team and the company.

Ideally, a virtual team’s mission should resonate with each member’s values — both as individuals and as professionals who want to develop their skills — and be of clear importance to the company.

![[image]](https://i0.wp.com/sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/BI-AA051_COVER_20070614163401.gif)

We found that when virtual teams really buzz, it is because they are ignited by a question or a task so compelling and exciting that people from across the company are drawn toward it. This happened, for example, at BP when, more than a decade ago, former Chief Executive John Browne asked everyone in the company how BP could become what he termed “a force for good.” His question sparked a whole host of virtual teams to gather around the question.

For example, one team of young people, the self-styled “Ignite” team, looked at the idea of trying to shift more energy production to sustainable resources, such as solar power and wind. It was this team’s energy and focus that resulted in BP’s early commitment to a sustainable-energy agenda.

The importance of meaningful work and inspiring visions is clear in the widely known results of two virtual teams: the collaboration that has produced the online encyclopedia Wikipedia, and the creators of Linux, an open-source computer operating system.

While neither is a company — each is made up of large numbers of volunteers — both owe much of their success to having inspired a sense of devotion and mission among their team members, or contributors. Both have ignited energetic and innovative communities with compelling and powerful questions: How do we create a way of bringing the wisdom of the world to everybody? And how do we build an open-source operating system for the world?

10. When building a virtual team, solicit volunteers as much as possible.

As Wikipedia and Linux have shown, virtual teams appear to thrive when they include volunteers with valuable skills — people whose proof of commitment is their willingness to join the team on their own.

Nokia, for one, sees a connection between a virtual team’s success and its openness to volunteers. The company says a significant portion of its teams that are working on strategic challenges of the future are made up of people who volunteered for the task.

—Dr. Gratton is a professor of management at London Business School. She can be reached atreports@wsj.com

INTERCULTURAL BUSINESS GOLF

Ashley Charles Jenner

Imagine the great Eye in the Sky assessing the behavior of Chinese and Indian businessmen playing golf under competitive conditions – a type of group dynamics environment. A four hour game of golf creates the random microcosmic conditions which bring the players´ true qualities to the surface. These conditions include such social, creative, judgmental, leadership and sporting skills as well as character tests. For Westerners, golf is an everyday fact of life. Indians have familiarity with the sport but the phrase Chinese Golfer is almost an oxymoron. How might non-westernized Chinese and Indians react to golf?

Groupings

Social factors come into the forefront when choosing the foursome. It can be expected that the Chinese may wish to play with other Chinese but that the more cosmopolitan Indian may feel confident about mixing with other nationalities. Both may end opting for family members as golf partners, just like in business. In fact, where there are a sufficient number of them, Asians in general even tend to take over entire golf clubs and adapt them to their culture and language, reminiscent of the English colonial compounds reserved for westerners in the 19th century. If this concept is extended to the corporate Board Room we can only expect a token westerner or two and a highly centralized decision making process in Chinese and Indian companies where seniority is known to be primordial. As far as business counterparties are concerned it can be expected that the low lying fruit will be offered to companies of the same nationality and only the less attractive deals may be available to outsiders. However, this has been known to happen in many European countries.

Playing style

During the game, risk-takers are clearly discernable from defensive players who are protecting their scorecard. Risk-takers aim for the flag with long shots across lakes but defenders place their ball just before the lake (lie-up strategy) so their next shot is safer. The Chinese may be categorized as avid risk-takers in contrast to the more prudent Indians. The modern Chinese business style reveals an irresistible force confident in its ability to conquer any market it chooses whereas the Indians display much more reserve. and target only certain industries. The exception may be the steam-roller approach of some of the Indian steel barons.

Club staff

Club members unquestionably follow the directives of club staff, no matter how rich and famous they may be. This is because staff tend to stay on for many years and become part of the family and also because failure to heed their words can result in membership suspension. This egalitarian treatment includes caddies. Players talk to the caddy about “our ball”. (Vital inclusion for good golf). It is difficult to see either the Chinese or the Indian (with their jāti system) feeling at ease with this treatment. In fact, the class structure could make it difficult for either one of them to see the caddy as being little more than a rickshaw cabby. Time will be needed for such social structures to fall away. In the USA of the1920´s, professional golf players such as the great Walter Hagen were not allowed to use the same changing rooms as the amateur “Gentlemen” golfers. In the same way that economic development did away with the western class structure, so it will with social stratification in Asia.

Talking shop on the course

Golf rounds are wonderful opportunities for doing business as they last about four hours and many senior executives play. However, direct selling to a CEO during a game can be disastrous. The best route is to get his phone number and call him during the week. The question is whether the Chinese and the Indian can resist the instantaneous hard-sell route by following the slow road. The latter is more the Chinese and the Indian oriental style where relationships are developed more carefully and this can produce a good golf-based business relationship dividend. However, socializing at the “19th hole” (the bar) with partners after the game is almost mandatory. It is usually difficult for reserved people to completely relax and participate actively in group idle shooting the breeze which can jump from one subject to another without warning and probably involves unfunny and even risqué jokes. The reserved Asian approach is at a definite disadvantage here although the Indians are known to be good, albeit rather verbose, raconteurs once they get into the groove.

The Rules of Golf

In golf, every shot must be counted. Normally a member of the group keeps score and the answer to the question “how many strokes?” is a test of character. Hard-liners own up to the true score and social players want to lop off a stroke or two. The scorer is also tested by an overtly false score, since he will have to sign the scorecard later. It is difficult to judge how either the Chinese or the Indian would act if no-one was looking when his ball was under a tree-root. Their behavior here has relevance to their business practices. Their version of truth is one of the greatest dividing factors between Asians and hard-nosed Westerners. Discretion is often seen as evasiveness. Chinese and Indian observance of contracts and copyright laws leaves room for improvement although Indians claim that their products are purely Indian intellectual property whereas the Chinese might find it difficult to make any such claim. The pressures of economic expansion appear to have warped some of the key traditional cultural values of these two great ancient civilizations as much as it has done in western countries.

Betting

Betting is common in golf, ranging from $1 a hole to $100 for a single put. Betting means that everyone counts all the shots. Handicaps (the stroke advantage a good player gives to a less skilled player) are paramount because if they are too high, the less skilled players will have an unfair advantage. Some players systematically keep high handicaps in order to win bets and even tournaments. Golf is all about trust but cheaters soon get caught and become golfing pariahs. The Chinese like to bet and would probably embrace golf betting foursomes but the Indian may shy away from the practice. Both groups may have some problems in grasping that winning money is secondary to playing the sport. This may be translated into a business concept of governance and sustainability which sets external constraints on money-making activities. Western companies are forced to follow constraints by activist groups but the BRIC´s in general do not suffer the same pressures.

Slow play

It is no coincidence that golf is the number one sport for business executives. It may be said that the mere fact that a person plays golf is already a virtue and subconsciously the player tends to incorporate the core values of golf into everyday personal and business life. The post-war Japanese experience is an example of this. Golf is all about facing uncertain adversity under the scrutiny of third parties within a framework of extensive rigid rules and etiquette without bending them in spirit or letter. Businessmen the world over eagerly look forward to seeing the enlarged ranks of Chinese and Indian golfers.

The 10 Best Companies For Women In 2013

Got your eye on the corner office? These companies offer women the best chance of getting there.

The National Association for Female Executives (NAFE), a division of Working Mother Media, this week released its annual list of the top 50 companies for executive women. While only 4% of America’s major corporations currently have female CEOs, this list spotlights the businesses that lead the nation in their commitment to female leadership.

“This year we see measurable progress for women at companies that have made their advancement a priority,” says Betty Spence, president of NAFE. “For women, these are the top companies to work for.”

The 10 Best Companies For Women In 2013

IBM

Percentage of female senior managers: 27%

The National Association for Female Executives (NAFE) named these the top 10 companies for executive women based on their commitment to women’s leadership. To be considered, companies needed a minimum of two women on their boards of directors and at least 1000 employees in the U.S. They were chosen based on female representation at all levels, access to and usage of programs and policies that promote the advancement of women, as well as the training and accountability of managers in relation to the number of women who advance in the company.

To be considered, companies needed a minimum of two women on their boards of directors and at least 1000 employees in the U.S. They were chosen based on female representation at all levels, employees’ access to and usage of programs and policies that promote the advancement of women, and the training and accountability of managers in relation to the number of women who advance in the company.

Among the top 10 companies for women’s advancement, IBM stands out. In 2011, 30-year IBM veteran Virginia Rometty was tapped as CEO, becoming the first woman to head the century-old tech giant and one of a tiny percentage of women leading major U.S. companies. Additionally, 27% of IBM’s senior managers and 23% of its corporate executives are women, and according to NAFE, more than 12,000 women are currently in the executive pipeline.

Health-care company Abbott also ranked in the top 10, thanks to a concerted effort to advance more qualified women. In the last decade, the numbers of women in executive management roles at Abbottincreased by a whopping 77%. Moreover, NAFE discovered that women represent 42% of the executives in profit-and-loss positions and comprise one third of its board of directors, which is significantly higher than the national average.

Other top-10 NAFE notables include General Mills, where 96% of female employees surveyed say they would recommend the food-manufacturing company as a good place to work; consumer products company Procter & Gamble, which offers flexible scheduling, mentoring programs, and job training taught by its CEO and other top executives; and financial services corporation Prudential Financial, where women represent the majority of employees studying for the firm’s on-site MBA degree.

Follow me on Twitter, Facebook and Google+.

More on Forbes:

The Best-Paying Cities For Women In 2013

http://www.ted.com/talks/naif_al_mutawa_superheroes_inspired_by_islam.html

http://www.ted.com/talks/naif_al_mutawa_superheroes_inspired_by_islam.html